I don’t remember when I bought the book. All that I know is that it was somewhere between many-months-ago and sometime-this-year—as if that’s telling, as if it’s not late October that I’m writing this. I also remember that I continued looking upon it with reverence even after it’s lost its place in my bag due to I didn’t have time to read it, because, for some reason or other, I had a wonderful few days for the time I did have it with me (perhaps also the reason I didn’t really get to read much—an auspicious harbinger that brings itself).

But there was something beyond my modest understanding that pulled me towards it even as I was stood in the Oxfam I got it from. To my shame, I must admit I had not heard of Raymond Carver at the time—not in a way that made the name stick, at least, as I came to find out I had several of his poems saved on my phone. But, according to those more well-read than me, there is some providence of sorts (and a bit of having read more lit crit than lit) guiding my hand when I pick books I’m otherwise unfamiliar with. Besides, Picador’s selection has proved itself steadily reliable time and again in matching my taste and I was trying to read more short stories. The reviews on the back spoke of both a “terrible silence” permeating his stories and extraordinary clarity and levelness in describing the ordinary. Sold, I and the book alike.

I finally came to read it last month, after someone of otherwise dubious standing found a sure standing in my studio while i was in Tunis, dug it up from one of many piles of books, and proclaimed it’s made him want to build himself a placidly unremarkable life. He was quick to follow up that he probably won’t, but the flame was there. (But this isn’t a memoir, or you’re not here for one at least; if I carry on like this, you might, by the end of this review, come to know me more intimately than some of my friends.) There, but for the grace of God, goes something relevant.

The book opens with the essays, first of which was Carver’s tribute to his deceased father. It’s touching and poignant, without being overly sentimental (which is perhaps an awful thing to say to someone not managing the feat: you’re grieving your dead parent and a Balkan bitch accuses you of sentimentality—and it’s not even lyrical).

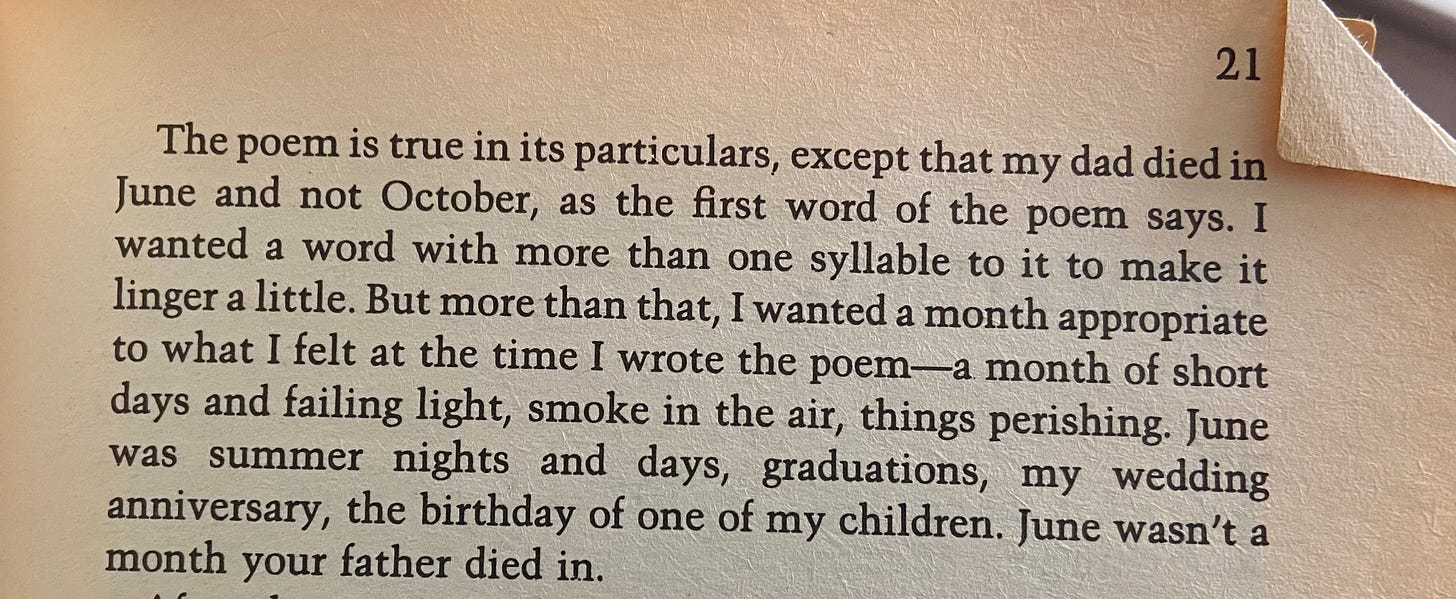

There was a line in particular that stuck with me. June wasn’t a month your father dies in. Whether it’s that in June of this year my father got diagnosed with stomach cancer (good prognosis and he’s had his last chemo session on the 14th of October, but stomach cancer, nonetheless), whether there is a real poetic merit to the words, neither of these are reason enough for the phrase to be as striking as it is, not for me and not for anyone else. Rather, its mightiness comes from somewhere else; in its simplicity, in its succintness and rawness, it lays out a lucid and denuded truth: June truly isn’t the month your father dies in.

I believe it is such considerations that then grant Carver’s writing the clarity everyone, himself included, praises. There is candour and there is perspicuity in his speech, and for that they demand little poetic ornament.

That isn’t to say his language and phraseology have no merit. He held The Word as a unit of speech in admirably high regard; he contends that the word is all we have, which is why we can’t really afford to use the wrong ones.

While I’m closer to Clarice Lispector’s not much different philosophy in Neart to the Wild Heart, that we only have words but words continue to lie, I agree with the general rallying for exactness as a prerequisite for fidelity and, essentially, life.

When Carver talks about John Gardner, writing, and being taught writing by John Gardner, he insists on preciseness of word choice, preciseness of word necessity. And because he is true to his word and practices what he preaches, he treads around vocabulary meticulously. But he also does so a bit gingerly at times: his words are faithful and truthful, yes, which is why the truth they hold doesn’t dwindle in light of chosing this or that. His becomes a simple yet deeply involved, limpid literature. But, while his writing remains uniquely charming, the gospel of his words could sometimes be punctuated by a more Specific term, a more convincing denominator.

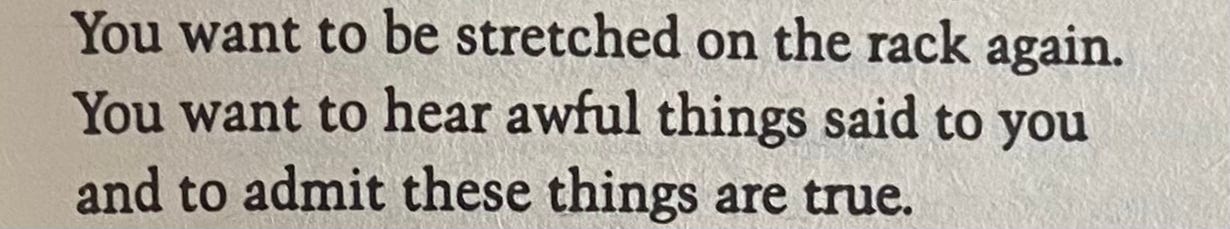

His poetry is for the most part in the approximate range of good—either direction from there. At its worst, it falls a bit flat and is rather unimpressive. At its best, he brings a modest glory to the everyday.

His despair doesn’t circle the drain too closely, and that’s a remark as neutral as some of his poems left me. That being said, it’s not always sunny in Carver’s literature. The “gritty realism” he’s known for becomes manifest in a few of them, squandering worldliness. (Like a milder, verse-only Tallahassee.)

They’re also visibly written by a storyteller, and that, too, is rather neutral; I personally enjoyed it. You’re not spoon-fed a denouement, which allows for a sense of hope to near-pervasively permeate the narrative—even the more laden ones.

Yes. I still found the selection in Fires more suffused in warmth than the sordidness in the rest of his work everyone talks about. A daily, mundane tenderness he knows how to do.

Other highlights among his poems were:

Drinking While Driving

Photograph of My Father in His Twenty-Second Year

Poem for Dr. Pratt, A Lady Pathologist

Morning, Thinking of Empire

(Need I mention, as a closing remark, that what normally qualifies as a good poem for me is the result of either a light liking of it in its entirety, or an utterly marvellous line or two. Because the last poem mentioned is a gracefully balanced blend of both, here it goes in all its splendour.)

This isn’t a review as much as it is a reading log accompanied by the odd thought. Regarding his short stories, I could talk about his adroitness with prose fiction, but I would be mostly repeating myself—for most of the previous remarks are here only augmented by this being the medium in which he was most at home.

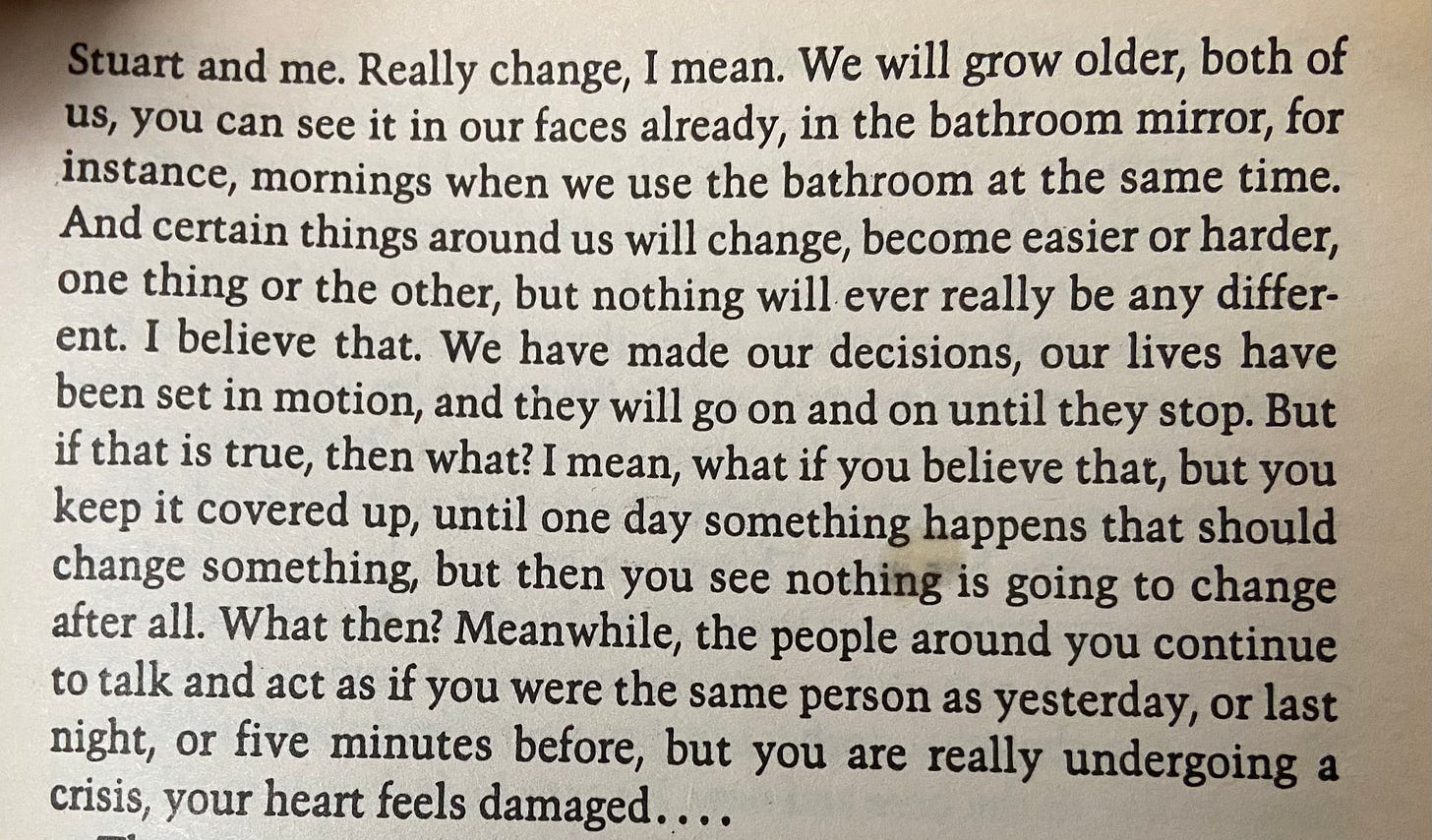

Among this collection, it was probably So Much Water So Close to Home that stood out the most. One could almost read it as a treatise on marriage, or: on simply knowing (like, really knowing) the person next to you.

Because So Much Water So Close to Home’s Claire knows; she doesn’t know, not materially, but—maybe in the marrow of her bones, maybe in the furrows of the subconscious in which the other can recognise the Being of the other, with its modes and habits and motives, before the other comes to it himself, or maybe she’s not an idiot and she just pieced out the more palpable pieces—she Knows.

Her husband also knows. It’s not explicated, thankfully, but it’s terribly explicit: He knows. I could laugh in his face. I could weep.

One can think of it as the anatomy of a marriage; of knowing the one next to you; on what it means being a wife, what it means being a husband; on what it takes to be happy, how easily that can be shaken up then away, and what the price of it is. For a sense of seriousness to any of these interpretations, I could even circle back to Carver’s mastery lying in his ability to pierce right to the truth that is the human heart. But I would be redundant and perhaps cloying (like a guy who just discovered realism…), so I probably shouldn’t.

Because, the thing is, one can read the story like that—read into it like that, that is. But Carver’s writing is elective, which means that one can also read it as the story of a couple, and then this happens, and it’s a terrible, terrible thing, and there’s still some tenderness to it all, there’s some cruelty, too, and he’s somewhat of a dickhead, but, ultimately,

life goes on.