It’s not The Recognitions.

A generous stranger might be prompted to believe I made good use of my exactly three months of inactivity; the kind of good use reading a nine-hundred-something page novel might be. However, my equally generous, albeit in different ways, friends would tell you what I kept telling them: that I’ve been working on my thesis, which has nothing to do with The Recognitions, or Gaddis, or American postmodernist fiction in general.

But Carpenter’s Gothic is, luckily, a book you (I) can say more about than just what it is not. For a start: it’s the first book I’ve taken with me on holiday that’s served its respective purpose effectively and appropriately. I’m too sensible to repeat an anecdote that half of you have probably heard already as to how Bataille’s Story of the Eye, of which at the time I only knew its slenderness and status as Literature and Evil author’s most well-known book, was going to tenderly, adoringly even, deliver me from the beaches of Sardinia last year; or, how my concern I’d be a prolific reader was, against the odds of seven people dear surrounding me at all times, so dire it could only be assuaged by Ulysses as a back up. DM me for more carefully picked beach reads.

Although the longest reading stretch of vacation-Gaddis only covered the fourty or so minutes I spent in a café by myself, separated from my peers because I insisted on sitting in the Moroccan midday sun, hampered then by my ears’ ringing because of said sun, I read enough as to want to finish it once I was back on stuck island stuck time.

The prolonged point-turned-smudge here is that it was, in spite of fragmented reading spurts (all me), and in spite of interrupted, seemingly disorienting unmarked dialogue or scene changes (all Gaddis), very easy to follow and get absorbed by.

A satire where the setting reflects proselyte, imperialist America just as much as the characters and their expositions lay it out directly and indirectly, its locus is a rural gothic house: 19th century Goth Revival’s sweetheart, an ostentatious and superficial emulation, this vernacular style takes the most obvious motifs, drizzles them around with reckless abandon, and takes no heed of structure, proportion, or logical relationships. Despite the difficulties arising in its imitative imposition on small domestic buildings, or the poor craft, it does make for a relatively pretty outside, apt to bring a tear to the naive Americana aesthete’s eye, with the same force an asymmetrical pediment, or a portico difficult to justify could deeply move a Twitter Retvrn guy.

Almost immured within the house’s perimeter is young heiress Elizabeth, in unceasing interaction with the three men in her life, one more rapacious and self-serving than the other: her husband, Paul, the archetypal conservative, a profiteer-hopeful of church business and a kid’s death, naggingly by her side primarily for a trust fund she doesn’t have access to; her brother, Billy, a New Age pacifist-radical, with no responsibility for his life, whose visits are invariably marked by an attempt to borrow money; and her evasive landlord and lover, McCandless, a bleeding heart liberal, stuck in a perpetual state of “cleaning up” past actions. To the latter belong the novel’s most long-winded and eloquent orations against creationism and neo-colonialism, and perhaps the most subtly presented critique between the archetypes portrayed: liberalism’s notorious clarity and knowledge to single out that which is wrong, paired with the inseparable cowardice to do anything about it.

The majority of them remain, however, characters, and don’t venture much outside of the respective categories they ironise. Paul is unequivocally antagonistic for the duration of the entire novel, albeit Elizabeth and McCandless’ tug of perception-war, namely whether he’s actually pulling any strings or is a puppet himself, is quite invigorating. Billy is never really transported beyond a humorous punching bag who doesn’t quite get the spirituality he’s preaching. While Elizabeth could’ve easily been the most complex of them all, what with the vacillation between her own dissimulations and what appears to be a sincere simplicity, it’s never quite explored to its full extent; although her enigmatic presentation is mostly intriguing and at times delightful, perhaps less left to the imagination would’ve had a stronger effect. Even McCandless, by far the most elaborately fostered of them all, ends up stuck in an iterative rant—a mostly astute one that also convinces one he’s also Gaddis’ darling and write-in—that stretches for a few pages too long and tedious.

This might in part be because the examination and the condemnation of the social and political tendencies under scrutiny here aren’t anything new, weren’t in the 80’s either: who doesn’t know it’s madness coming one way, and stupidity the other? However, Gaddis’ remain charming and refreshing insofar as they are still written in his emblematic style, replete with signs, symbols, and irony. Repetition remains both his closest friend and most impassioned foe.

On one hand, some of the moments come across as almost redundant. How many circles can one do before they get vertigo? Or, worse yet: bored. Although the majority of such moments are eventually mediated by an impressively potent humour, or the reality of domestic life ever so grittily depicted, the book isn’t, at least at times, ensured against losing the reader’s interest.

But, on the other, the text doesn’t seem concerned with such considerations. The intentionality and obstinacy with which Gaddis confines his characters to their stringent moral classes knows neither hesitation nor repose. Such persistence is a feat in itself, even more so as it is the very same unwavering repetition that grants the comical moments their comedy: after three different people think, at refreshing intervals, Paul’s diagram a child’s scribbling, one can’t be too upset when a fourth sees and recalls the Battle of Cressy at what would otherwise be annoying length.

The fidelity and granularity of such unsophisticated, mundane interactions, even when they aren’t punchlines, is another of the novel’s fortes. The simplest devices in his repertoire are among the most striking. As everything else here is interrupted, so is Elizabeth and Paul’s incontestable misery as a couple, many instances of it coming in the middle of arguments and contentions in the form of a short, curtly answered then promptly forgotten do you want peas with it, a mere food category yet whole far cry away from Frank O’Hara’s wouldn’t you like the eggs a little different today. Belonging to entirely different worlds governed by entirely different psychosexual and romantic laws, it’s the poem turned on its head. But it’s not the syntactic similarity that’s disconcerting, inasmuch as how the both of them could either stand together, or not stand at all, but also together, as plausible, if tangential, answers to Agnes Varda’s theorising around Le Bonheur, or rather: what it means to be a man, what it means to be a woman.

That is to say: is there an inescapable violence in that which is most loving and lovable, or were one to scour even the most vicious, opportunistic of places, they would find a glimmer of love?

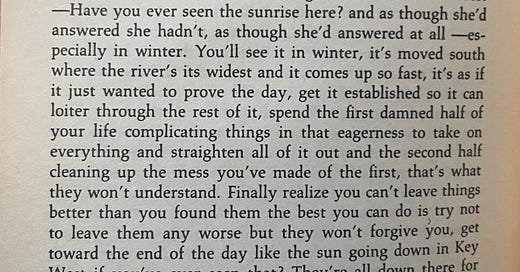

Also among the instrumental highlights stands the truistic tautology used to describe a brief moment of intimacy between Elizabeth and McCandless; at the end of the day, little else than a comparison between a moment happening and a hypothetical gesture half a degree of circumstance different:

his hand on her knee there as it might have been his hand on her knee under the tablecloth as the wine was being poured.

The abruptness with which the reader is thrust into their affair also stands as proof of how both intimacy and the action at large unfold off the page in Carpenter’s Gothic. Obstructed either by access to just the lesser half of a telephone’s call, or by simply a chapter starting in media res with someone’s mouth on someone else’s skin, everything is already in the process of happening and becoming for Gaddis, yet comes in has happened/will happen dyads of stark contrasts, everything in between thus excluded. Through this most brazen omission, that seems to attempt evading the now, jump from imperfect past to less than perfect future, it is exactly the present, the now, that is being foregrounded.

The O’Hara comparison might’ve been inapposite; its emergence emotional and visceral, yet its inclusion here self-indulgent. Reorienting towards Gaddis’ contemporaries for more coherent a commentary, he finds himself at the polar opposite of the other paragon of American postmodernist literature. While John Barth’s is the imperceptible transition from night to day (or at least the simile of it), Gaddis is discerningly romping with the light switch in a windowless room, putting on a show most diverting.

It’s not The Recognitions, and aren’t I ever so lucky for it? If the two are anything similar, I’ve only exhausted about two hundred pages of it, with nine hundred to go.